THE GOTHIC PERIOD

The Gothic cathedral

« Gothic architecture comes after Romanesque architecture in the same way as the flower comes after the bud » (Auguste Rodin).

The decision to build a new, larger cathedral, particularly with a more spacious chancel, was taken by Aimeric de la Serre, bishop of Limoges from 1246 to 1272, who devoted his fortune to this construction. Thanks to this considerable donation (over 27,000 livres) the building costs were covered for17 years. But this great patron died before the building started and it was Hélie de Malemort, dean of the chapter, that lay the first stone on June 1st, 1273, during the vacancy of the bishop’s seat.

This building period must have been very active, all the more as the fine granite used came from the quarries of Neuplanchas, in the parish of St Jouvent, 20 km north of Limoges. In 1290, all funds having run out, bishop Gilbert of Malemort found new resources to ensure that the work went on. His successor Raynaud de la Porte extended for 6 more years the donation of the revenues of the vacant parishes. The work went on under both his successors, Gérard Roger and Hélie de la Porte, but came to an end in 1327. At that date, the apse, the chancel and its ambulatory and radiating chapels, as well as the north transept chapel, had been completed and linked to the Romanesque transept.

In 1344,Gui de Combon being bishop, new funding sources were found and Avignon Pope Clement VI, born in Limousin, granted indulgences to those of the faithful whose generosity would help towards the building. The façade and the south transept rose window were erected but the works were interrupted because of the war against the English, and in 1370 the Black Prince sacked and burnt down the City. When peace returned, Gregory XI -third Avignon Pope and Clement V’s nephew- helped towards the repairs but it was not until 1468 that the works could be resumed, thanks to the City Consuls’ generosity : the transept western walls were finished, the first two bays of the nave were erected and completed in 1499.

The fine Portal of St John -which constitutes the transept north façade- was built and sculpted during the first third of the 16th century, Philip de Montmorency and Villiers de Lisle-Adam being bishops (their coats of arms can be seen on this very façade, close to those of the chapter).

Around 1537 Jean de Langeac undertook the completion of the nave. His death interrupted this work, which did not go further than the foundations.

It was not until 1847 that Mgr Buissas had important restorations undertaken in the whole of the edifice and the north transept façade completed with the upper gallery, its gables and pinacles.

Lastly, in 1876, Mgr Duquesnay saw to the completion of the cathedral. The last three bays were finished in 1876 with the narthex connecting nave and tower . In 1888 the roodscreen was re-located to the church entrance, thus making it possible to pull down the wall that had closed the nave with its bearing out stones since the end of the 15th century. On 12th August 1888, Mgr Renouard inaugurated this slender, tall, magnificent edifice.

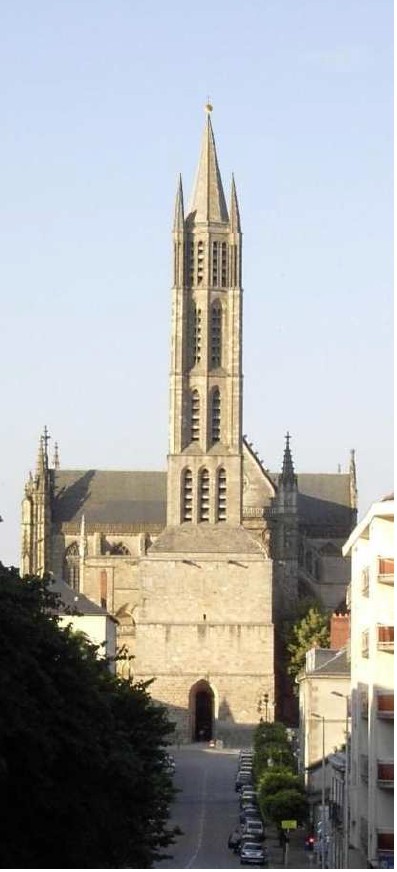

The Gothic Bell Tower

The history of the bell tower is independent from that of the ogival cathedral as its transformation had come before the latter was built. As seen above, from the Romanesque tower were only left the narrow porch and the two storeys above it, caught in a huge mass of masonry. The four upper storeys were begun in 1242, 30 years before the Gothic church started being used. Probably at that time the upper part of the Romanesque tower was falling apart and in need of rebuilding, but, as the church vaults were leaning onto the tower, the lower part of the tower was kept to be used as a base for a new tower in the current taste.

The new tower is early Gothic in style and of a particular Limousin type with its corner turrets similar to those of Saint Michel-des-Lions and Saint Pierre-du-Queyroix, for which it was taken as a model.

The first storey is square like the Romanesque base, with three high windows on each side. Above, it is octagonal. Square eight-sided turrets rise up from the angles of this to the base of the former spire : they are pierced only at the last storey and originally ended in pyramids the bases of which are still visible.

Each façade of the octagonal storeys has a high window; in each window on the third storey there is a mullion and each window on the fourth is divided into two lights.

To support this surprising tower rising up to 62 m above ground level and its spire (18m high) it was necessary to reinforce the Romanesque base with inner bulky masonry set in the porch reentrant angles ; the lateral passages were not kept , all arcadings were doubled : thus the Romanesque part, with its arcades, did not lose its elegance. But in 1372 there were fears that the north west angle might crash down so that the whole base had to be covered with a thick stone wall to maintain the structural solidity of the whole building. Yet it had lacked solidity for in 1431, the coating wall showing large cracks, the whole of the southern façade had to be done over.

In December 1443, a powerful hurricane damaged the high spire and the pinacles. On April 25th 1483, a storm destroyed the stone spire. It was replaced by a lead-covered wooden spire which was struck by lightning on June 30th, 1571.The tower wooden beams were burnt down and the eleven bells inside melted down or broke in their fall. In 1574 the tower was restored but left without a spire (of which only the toothing stones can be seen to-day). In spite of its awkward-looking base and the absence of a spire it remains a slender, tall, fine tower.

cliché et montage Jacques Perrin

The work of Jean Deschamps

« The language of monuments is sometimes clearer than documents »(Émile Mâle)

Towards the middle of the 13th century Gothic art moved down from the North and the province of Île de France to the southern part of France where, on the whole, the builders remained faithful to single-nave buildings, with a wide nave and buttresses between the side-chapels. Thus rose successively the cathedrals of Clermont-Ferrand, Narbonne, Limoges , Toulouse and Rodez. Documents related to the former two give the name of the master of works, Jean Deschamps ; but the other cathedrals also definitely bear the stamp of this architect’s genius.

Born around 1218 probably in the Picardie region, Jean Deschamps had worked on various building sites in the North, and also with Pierre de Montreuil during the building of the Sainte Chapelle in Paris. He came after the generation of the great architects who had built Chartres, Amiens, Rheims, Soissons and Saint Denis; this explains why, in his work, can be found imitations of the northern cathedrals side by side with numerous original aspects and innovations.

In Limoges, as in Clermont-Ferrand, same proportions, same harmony : inside, the heigth is divided in two roughly equal parts. Same bundles of small columns rising straight up to the base of the vaults ; same triforia integrated in the windows like a shadowy frieze under the bright stained glass windows ; same windows, slightly reduced in size so as not to fill the whole width of the bay ; same sobriety in the ornamentation , because the hard Limousin granite, like the lava from the Auvergne is not easy to cut and carve.

At the entrance of each of the radiating chapels, around the chancel, is to be seen a similar straight small bay which gives them more depth. Besides, if one compares the building plans for Limoges and Clermont, established on the same scale, both chancels with their chapels and ambulatory coincide pretty exactly. Moreover, in both cathedrals, the diagonal ribs come down into the wall above the capitals, which increases the impression of lightness and already announces Flamboyant Gothic.

Jean Deschamps’s similar innovations can also be found outside. The triforium gallery, instead of going through the pillars, as was usual, winds round them so as not to impair their solidity ; a succession of imbedded turrets can be seen under the buttresses. The chapels are not covered with the usual roofing but with a wide terrace. The balustrade crowning them goes round the buttresses thus creating a graceful balcony all around the church. As for the hollowed out flying-buttresses, presenting a row of small columns, their abutments look lighter and the archivolts in the chevet windows are decorated each with a very fine pierced gable.

The proportions of the whole cathedral are surprisingly just ; though it cannot compete with the grandeur of the northern cathedrals, it generates a sense of depth and height in all its parts. At first, one is surprised by its simplicity and sobriety, then delighted by its pure, elegant lines and volumes. All superfluous ornamentation has been discarded, every element unnecessary for its stability has been avoided. The capitals are reduced to single or double carved rings, and no formeret (i.e. an arch linking vault and walls) is to be seen except in the northern bays of the transept.

The transept, being narrow, does not make a wide gap in the perspective of the nave : its crossing is not based on a square ground-plan, which is the case in most cathedrals. Yet Jean Deschamps’s original ground-plan for the crossing must have been based on a square, as in Clermont-Ferrand, as can be inferred from the study of the left pillar at the chancel entrance: above the capital the two springings of the diagonal ribs are clearly visible, false springings made of a few toothing stones jutting out of the present rib.This disalignment is clearly an evidence that the first building campaign had come to an end and that when work was resumed, as the transept had been erected over the narrow bases of the old Romanesque transept, it was necessary to consider an alteration of the curves for the new ribs. Apparently this is the only important alteration in the whole edifice.

Jean Deschamps, a master of works who established Gothic art in the south of France, can be considered as one of those 13th century great creators who never built an edifice without architecture progressing by it.

***